Coliseum Is On Its Way Out. But Wait.

New York Times Publication Date: Sunday August 03, 2003

Photos: Dick Walsh, right, of the Coalition to Save Our

Coliseum, and Alan Organschi, an architect, look over a proposal for the New

Haven Veterans Memorial Coliseum. (Photographs by C.M. Glover for The New York Times)

To these detractors -- everyone from longtime residents to occasional

highway passersby -- the decision by Mayor John DeStefano last summer to

tear the building down to save the city money was met with a collective

sigh of relief.

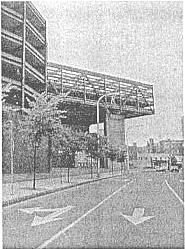

"The Coliseum was one of these 60's redevelopment projects that people

thought did a lot of damage because it took out an older neighborhood

and replaced it with a concrete-and-steel monolith," said Tony Bialecki,

New Haven's deputy director of economic development. "When the building

finally comes down, people will be pleasantly surprised."

Well, not everyone. A group of citizens who want to spare the building

from the wrecking ball are pressing the mayor to realize the

Coliseum's ugly-duckling potential and transform it into a thing of

beauty. Called the Coalition to Save Our Coliseum, the group has pulled together a vocal and well-connected, if unexpected, 100-member mix of sports buffs, housing advocates, urban historians, and architecture professors, who are fighting to keep the

9,000-seat arena standing.

"Our point of view is that the city moved too quickly, that the only

option was to demolish the coliseum ," said Anstress Farwell, president

of the New Haven Urban Design League and who backs the coalition's

cause. "This will destroy a huge part of the city, and the people who are

deciding to do it won't be here in 20 years."

Conceived nine months ago over a table at a fast-food restaurant, the

group in June drew about 50 people to a symposium that featured a

half-dozen alternate architectural plans for the building and its seven-acre

site, where the city proposes to move the Long Wharf Theater and build

a hotel, conference center, apartments, stores, and plaza, for $400

million.

While the city solicits bids for the Coliseum's demolition, which could start as soon as December, and awaits a $10 million bond from the state to pay for it, the coalition is trying to raise a few thousand collars to put its message on a billboard along I-95. It has also scheduled another symposium for the fall.

Still, the argument will be the same: A development of this size is a foolhardy undertaking in these economic times. Plus, the building, with its tiles that are typically found on farm silos and inventive rooftop parking garage, has come to

be loved.

"Some people have called it a brutalism of architecture, but there was almost a family environment inside the Coliseum ," said Dick Walsh of Clinton, who serves as the coalition's secretary. "Destroying it would be a loss for middle-class people from the city and suburbs. Where else can we go for good inexpensive entertainment?"

For many coalition members, this entertainment was most memorably sports events. Mr. Walsh estimates he has been to the coliseum 500 times, mostly for Nighthawks hockey games. Others had a more involved connection, working for a team or selling T-shirts.

Yet the Coliseum's storied history as a music arena--a stop for the likes of Van Halen, the Grateful Dead, the Kinks, and Kiss -- holds similar sway over the building's champions.

When he was growing up in Litchfield, Alan Organschi frequently traveled to the Coliseum to see concerts, just one block away from where his architecture firm stands today, in the city's Ninth Square neighborhood. Mr. Organschi argued that the Coliseum should not be razed because it is an effective barrier against highway noise and provides 1,700 much-needed parking spaces for the train station and downtown. He's also afraid that the city will run out of funding for the new development and the Ninth Square, after rehabbing itself over the past decade, will be stuck next to a gaping hole.

Mr. Organschi, who teaches at the Yale School of Architecture, also said that, historically, it's been bad policy to rip down structures without considering that tastes, even for super-scale edifices, might someday change.

"We're reliving the same urban paradigms here," Mr. Organschi said. "It's about time we stopped having stylistic fetishes about buildings and started dealing with the potential for urban space."

Under his own proposal, unveiled at the symposium in June, the Coliseum would end up with mixed uses the way it was originally intended by the architect Kevin Roche, who went on to design many of the wings of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mr. Organschi would shrink the existing arena's size while adding a new theater, conference center, gym, and stores, for about $50 million, a fraction of the city's price.

Even those who haven't spent much time inside it said they believed the Coliseum should be preserved, such as Robert A.M. Stern, the architect and dean of the Yale School of Architecture.

Yet in an example of how the issue is polarizing New Haven's academic and political leaders, the mayor's office has chided Mr. Stern for his views, calling him an out-of-towner who doesn't have the city's long-term interests at heart.

"This is a national issue, not a provincial one," Mr. Stern said. "The preservation movement may have grown out of people worried about the destruction of Beaux Arts buildings, but the older generation needs to realize the grounds of battle are shifting."

Though the Coliseum has always stood out on New Haven's skyline since it opened its doors in 1972, it hasn't always stood on its own. It has never been profitable, which led to the city's decision in 1999 to turn the building over to a private event-management group, Philadelphia's SMG.

Yet despite luring a hockey franchise to the Coliseum , the New Haven Knights, SMG still couldn't make the building pay for itself. In the winter of 2002, SMG officials told the mayor's office they would need $1.4 million to cover their operating budget.

Around the same time, a city-commissioned study found that the building required an additional $30 million to bring it up to code, after the $5 million spent over the past eight years to improve scoreboards and locker rooms. In addition, the study claimed nearby sites like the Arena at Harbor Yard in Bridgeport and the casinos were consistently siphoning away big-ticket acts, further jeopardizing the Coliseum's ability to cover costs.

Firm in the study's conclusions, Mayor DeStefano announced on July 2, 2002 that the Coliseum had no choice but to close, and on Sept. 1, five days after the building hosted its last event, World Wrestling Entertainment, the city locked the Coliseum's doors.

Yet in many ways, a different type of show was just beginning, as the coalition started systematically and meticulously attacking the mayor's assertions.

Citing the mayor's own numbers, the group has stated that in 2001 the coliseum held 113 events, while in 2002, that number rose to 121, signs of improvement.Perhaps the most strongly worded accusation from the group is that the mayor acted unilaterally, showing poor judgment.

Mr. Bialecki, the deputy director of economic development, said that wasn't true. He said the mayor's office has been open to solutions for the Coliseum for years, but that nobody -- especially the city's outlying suburbs -- has been willing to help.

The fundamental problem, as Mr. Bialecki sees it, ticket holders were simply driving to the Coliseum , watching their game, then heading home without spending any money in the city. A site that appeals to more than just people who attend Arena Football and circuses, he argued, even if initially expensive, will be better off for New Haven in the long run.

"There are many tremendous artifacts in New Haven, and the city has been involved with the restoration of a lot of them where we can," Mr. Bialecki said. "But this just comes down to economic feasibility, and the coalition's numbers don't add up."

Mr. Walsh and his group are unfazed and said momentum is starting to line up behind them, as the state battled over a budget while funds dry up for urban development projects of this magnitude.

"If we keep talking, we think people will ultimately listen to reason," Mr. Walsh said. "This is clearly an injustice, and something needs to be done."

(END)